Early spring. There is a train in Russia. There is a lively conversation in the carriage; a merchant, a clerk, a lawyer, a smoking lady, and other passengers argue about the issue of women, about marriage, and free love. Only love illuminates marriage, says a smoking lady. Here, in the middle of her speech, a strange sound is heard, as if interrupted by laughter or sobbing, and a certain not yet old, gray-haired gentleman with impetuous movements intervenes in the general conversation. Until now, he had answered sharply and briefly to the neighbors' charm, avoiding communication and meeting, and smoked more and more, looked out the window or drank tea and at the same time was clearly burdened by his loneliness. So what kind of love, the lord asks, what do you mean by true love? Preference of one person to another? But how much? For a year, for a month, for an hour? After all, it happens only in novels, never in life. Spiritual affinity? The unity of ideals? But in this case, there is no need to sleep together. And, you, right, recognized me? How not? Yes, I am the same Pozdnyshev that killed his wife. Everyone is silent, the conversation is ruined.

Here is the true story of Pozdnyshev, which he himself told one of his fellow travelers, the story of how he, by this very love, was brought to what happened to him. Pozdnyshev, a landowner and a university candidate (he was even the leader) lived before his marriage, like everyone else in his circle. He lived (in his current opinion) depraved, but, living depraved, believed that he lives as it should, even moral. He was not a seducer, did not have “unnatural tastes”, did not make his life goals out of debauchery, but gave himself to him sedately, decently, rather for health, avoiding women who could tie him up. Meanwhile, he could no longer have a pure relationship with a woman; he was, as they say, a “harlot”, like a morphist, drunkard, smoker. Then, as Pozdnyshev put it, without going into details, all sorts of deviations went. He lived like this for thirty years, without, however, leaving a desire to arrange for himself the most exalted, “pure” family life, taking a closer look at the girls for this purpose, and finally found one of the two daughters of the ruined Penza landowner who he considered worthy of himself.

One evening they rode in a boat and at night, in the moonlight, returned home. Pozdnyshev admired her slender figure, covered in a jersey (he remembered this well), and suddenly decided that it was her. It seemed to her that at that moment she understood everything that he felt, and he, as it seemed to him then, thought the most exalted things, and in fact the jersey was especially to her face, and after a day spent with her he returned home delighted , confident that she was “the top of moral perfection,” and the next day he made an offer. Since he did not marry for money and not for connections (she was poor), and besides, had the intention to stay after the marriage of “monogamy,” his pride knew no bounds. (I was a terrible pig, but imagined that it was an angel, Pozdnyshev admitted to his companion.) However, everything went awry at once, the honeymoon did not add up. All the time it was disgusting, shameful and boring. On the third or fourth day, Pozdnyshev found his wife bored, began to ask, hugged her, she cried, unable to explain. And she was sad and sad, and her face expressed unexpected coldness and hostility. How? What? Love is a union of souls, but instead this is what! Pozdnyshev shuddered. Is love in fact exhausted by the satisfaction of sensuality and they are completely alien to each other? Pozdnyshev did not yet understand that this hostility was a normal, not a temporary state. But then there was another quarrel, then another, and Pozdnyshev felt that he was “caught”, that marriage is not something pleasant, but, on the contrary, very difficult, but he did not want to admit it to himself or to anyone else. (This bitterness, he later argued, was nothing more than a protest of human nature against the “animal” that overwhelmed her, but then he thought his wife was guilty of a bad character.)

At eight years old, they had five children, but life with children was not joy, but flour. The wife was child-loving and gullible, and family life turned into a constant salvation from imaginary or real dangers. The presence of children gave rise to contention, relations became increasingly hostile. In the fourth year they already spoke simply: "What time is it? It's time to sleep. What is lunch today? Where to go? What is written in the newspaper? Send for a doctor. Masha’s throat hurts. ” He watched her pour tea, put a spoon in her mouth, squish, drawing in liquid, and he hated it for that. “You have a good grimace,” he thought, “you tortured me with scenes all night, and I have a meeting.” “You are well,” she thought, “and I haven’t slept with the baby all night.” And they not only thought so, but spoke, and they would have lived like in a fog, not understanding themselves, if it had not happened what happened. His wife seemed to wake up since she had stopped giving birth (doctors prompted the means), and constant anxiety about the children began to subside, she seemed to wake up and saw the whole world with his joys, which she had forgotten about. Ah, how not to miss! Time will pass, you won’t return! From a youth, she was told that in the world one thing is worth attention - love; Having married, she received something from this love, but not all that was expected. Love with her husband was no longer right, some other, new, clean love began to appear to her, and she began to look around, waiting for something, again took up the previously abandoned piano ... And then this man appeared.

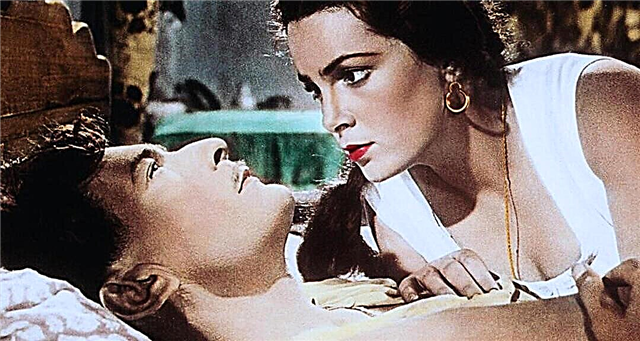

He was a musician, violinist, the son of a ruined landowner, who graduated from the conservatory in Paris and returned to Russia. His name was Trukhachevsky. (Pozdnyshev even now could not talk about him without hatred: wet eyes, red smiling lips, fixed mustache, his face went pretty, and his manners were made cheerful, he spoke more and more with hints and passages.) Trukhachevsky, arriving in Moscow, went to Pozdnishev He introduced him to his wife, immediately a conversation about music started, he invited her to play with her, she was delighted, and Pozdnyshev pretended to be delighted so that they would not think that he was jealous. Then Trukhachevsky arrived with a violin, they played, his wife seemed interested in one music, but Pozdnyshev suddenly saw (or he thought he saw) how the beast sitting in both of them asked: “Can I?” - and answered: "It is possible." Trukhachevsky had no doubt that this Moscow lady agreed. Pozdnyshev gave him expensive wine at dinner, admired his game, called for dinner again next Sunday, and barely restrained himself so as not to kill him immediately.

A dinner was soon arranged, boring, feigned. Soon enough, the music began, Beethoven’s sonata Kreitserova, the wife on the piano, and Trukhachevsky played the violin. The terrible thing is this sonata, the terrible thing is music, thought Pozdnyshev. And this is a terrible tool in the hands of anyone. Is it possible to play Kreutzer's sonata in the living room? Play, pat, eat ice cream? Hear her and live as before, without committing those important acts that music tuned in? It is scary, destructive. But Pozdnyshev for the first time sincerely shook Trukhachevsky’s hand and thanked for the pleasure.

The evening ended happily, everyone parted. And two days later, Pozdnyshev left for the county in the best of moods, there was an abyss. But one night, in bed, Pozdnyshev woke up with a "dirty" thought about her and Trukhachevsky. Horror and anger squeezed his heart. How can it be? But how can this not happen if he himself married her for this and now another person wants the same from her. That person is healthy, unmarried, "between them is the connection of music - the most refined lust of feelings." What can hold them back? Nothing. He did not fall asleep all night, got up at five o’clock, woke up the watchman, sent for the horses, at eight sat down in a tarantas and drove off. I had to ride thirty-five miles on horseback and eight hours by train, the wait was terrible. What did he want? He wanted his wife not to want what she wanted, and even should have. As in the delirium he rode up to his porch, it was the first hour of the night, the light still burned in the windows. He asked the footman who is in the house. Hearing that Trukhachevsky, Pozdnyshev almost sobbed, but the devil promptly told him: don’t be sentimental, they will disperse, there will be no evidence ... It was quiet, the children were sleeping, the lackey Pozdnyshev sent to the station for things and locked the door behind him. He took off his boots and, left in stockings, took a damask dagger from the curve wall, never used and terribly sharp. Gently stepping, he went there, sharply opened the door. He forever remembered the expression on their faces, it was an expression of horror. Pozdnyshev rushed at Trukhachevsky, but a sudden burden hung on his hand - his wife, Pozdnyshev thought it would be funny to catch up with his wife’s lover, he didn’t want to be ridiculous and hit his wife with a dagger in left side, and immediately pulled it out, wanting, as it were, to correct and stop what was done. “Nanny, he killed me!”, - blood gushed out from under the corset. “I got my way ...” - and through her physical suffering and the nearness of death her familiar animal hatred was expressed (she did not consider it necessary to talk about what was most important to him, about treason). Only later, when he saw her in a coffin, he began to realize that he had done, that he had killed her, that she was alive, warm, and that she became motionless, waxy, cold, and that it was never possible to fix this anywhere. He spent eleven months in prison awaiting trial, was acquitted. The children were taken by his sister-in-law.