Gustav Ashenbach on a warm spring evening of 19 ... left his Munich apartment and went on a long walk. Excited by day labor, the writer hoped that the walk would cheer him up. Returning back, he was tired and decided to take the tram at the Northern cemetery. There was no soul at the stop and near it. On the contrary, in the glare of the passing day, the Byzantine structure - the chapel - was silent. In the portico of the chapel, Ashenbach noticed a man whose unusual appearance gave his thoughts a completely different direction. He was of medium height, skinny, beardless and very snub-nosed man with red hair and milky-white freckled skin. A wide-brimmed hat gave him the appearance of an alien from distant lands, in his hand was a stick with an iron tip. The appearance of this man aroused the desire to wander in Ashenbach.

Until now, he looked at travel as a kind of hygiene measure and never felt the temptation to leave Europe. His life was limited to Munich and a hut in the mountains, where he spent a rainy summer. The thought of traveling, of a break in work for a long time, seemed to him dissolute and destructive, but then he thought that he still needed a change. Ashenbach decided to spend two or three weeks in some corner in the affectionate south.

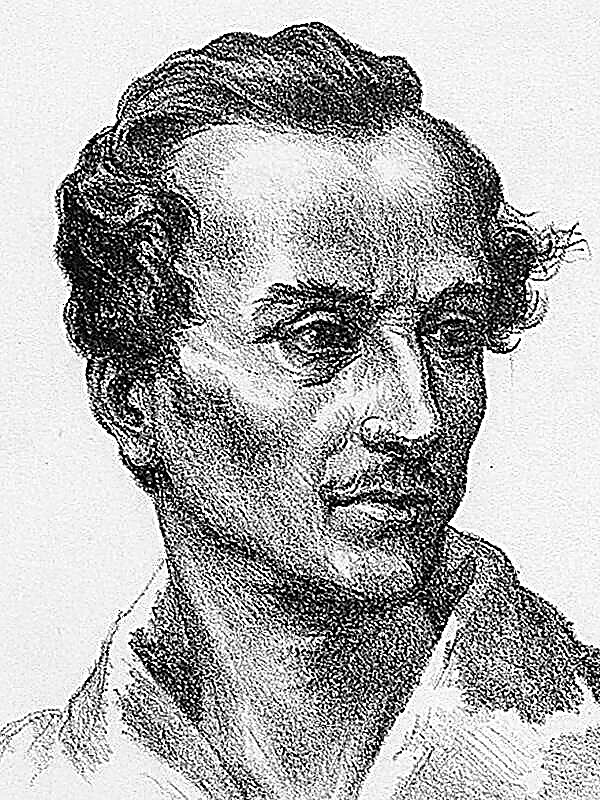

The creator of the epic about the life of Friedrich of Prussia, the author of the novel Maya and the famous short story The Insignificant, the creator of the treatise Spirit and Art, Gustav Ashenbach was born in L. - the county town of Silesian province, in the family of a prominent judicial official. He composed his name while still a gymnasium student. Due to poor health, doctors forbade the boy to attend school, and he was forced to study at home. From his father's side, Aschenbach inherited a strong will and self-discipline. He began the day by dousing himself with cold water, and then for several hours honestly and zealously sacrificed his strength in a dream to art. He was rewarded: on the day of his fiftieth birthday, the emperor granted him a noble title, and the department of public education included Ashenbach's selected pages in school books.

After several attempts to settle somewhere, Aschenbach settled in Munich. The marriage, in which he entered as a young man with a girl from a professor's family, was dissolved by her death. He left a daughter, now married. There was never a son. Gustav Aschenbach was a little shorter than average height, a brunette with a shaved face. His hair that was combed back, already almost gray, framed a high forehead. The shackle of gold glasses crashed into the bridge of the nose of a large, noble outlined nose. His mouth was large, his cheeks were thin, wrinkled, a soft dash divided his chin. These traits were carved by a chisel of art, and not of a difficult and anxious life.

Two weeks after the memorable walk, Aschenbach departed with a night train to Trieste to catch the steamer going to Pola the next morning. He chose an island in the Adriatic to relax. However, rains, humid air and provincial society annoyed him. Ashenbach soon realized that he had made the wrong choice. Three weeks after arrival, a fast motorboat was already taking him to the Military Harbor, where he boarded a boat going to Venice.

Leaning his hand on the handrails, Ashenbach looked at the passengers who had already boarded. On the upper deck were a bunch of young people. They chatted and laughed. One of them, in a too fashionable and bright suit, stood out from the whole company with his croaking voice and exorbitant excitement. Looking at him more closely, Aschenbach with horror realized that the young man was fake. Under the make-up and light brown wig, an old man with wrinkled hands was visible. Ashenbach looked at him, shuddering.

Venice met Ashenbach with a gloomy, leaden sky; it was drizzling from time to time. The disgusting old man was also on deck. Ashenbach frowned at him, and he was overcome by a vague feeling that the world was slowly transforming into absurdity, into a caricature.

Ashenbach settled in a large hotel. During dinner, Ashenbach noticed a Polish family at a nearby table: three young girls of fifteen to seventeen years old under the supervision of a governess and a boy with long hair, looking about fourteen. Ashenbach noted with amazement his impeccable beauty. The boy's face resembled a Greek sculpture. Ashenbach was struck by the obvious difference between the boy and his sisters, which was even reflected in the clothes. The outfit of the young girls was extremely unpretentious, they held on stiffly, the boy was dressed smartly and his manners were free and laid-back. Soon a cold and majestic woman joined the children, whose strict outfit was adorned with magnificent pearls. Apparently, it was their mother.

Tomorrow the weather did not get better. It was damp, heavy clouds covered the sky. Ashenbach began to think about leaving. During breakfast, he again saw the boy and again marveled at his beauty. A little later, sitting in a deck chair on the sandy beach, Ashenbach again saw the boy. He, along with other children, built a sand castle. The children called to him, but Ashenbach could not make out his name. Finally, he found that the boy's name was Tadzio, a diminutive of Tadeusz. Even when Ashenbach did not look at him, he always remembered that Tajio was somewhere nearby. Fatherly favor filled his heart. After lunch, Ashenbach went up in the elevator with Tajio. He saw him so close for the first time. Ashenbach noticed that the boy was fragile. "He is weak and painful," Aschenbach thought, "surely he will not live to old age." He chose not to delve into the sense of satisfaction and calmness that gripped him.

Walking around Venice did not bring Ashenbach pleasure. Returning to the hotel, he told the administration that he was leaving.

When Ashenbach opened the window in the morning, the sky was still cloudy, but the air seemed fresher. He repented of the hasty decision to leave, but it was too late to change him. Soon Ashenbach was already riding a steamboat along a familiar road through the lagoon. Ashenbach looked at the beautiful Venice, and his heart was breaking. What was a slight regret in the morning now turned into spiritual anguish. As the steamboat approached the station, the pain and confusion of Ashenbach increased to mental confusion. At the station, a messenger from the hotel approached him and said that his luggage was mistakenly sent almost in the opposite direction. With difficulty hiding his joy, Aschenbach declared that he would not go anywhere without baggage and returned to the hotel. Around noon, he saw Tadzio and realized that leaving was so difficult for him because of the boy.

The next day, the sky cleared, the bright sun flooded the sandy beach with its radiance, and Ashenbach no longer thought about leaving. He saw the boy almost constantly, met him everywhere. Soon Ashenbach knew every line, every turn of his beautiful body, and there was no end to his admiration. It was a drunken delight, and the aging artist greedily surrendered to him. Suddenly, Ashenbach wanted to write. He formed his prose on the model of the beauty of Tajio - these exquisite one and a half pages, which were soon to cause general admiration. When Ashenbach finished his work, he felt devastated, he was even tormented by his conscience, as after an unlawful immorality.

The next morning, Ashenbaha had the idea to make a fun, laid-back acquaintance with Tadzio, but he could not speak to the boy - a strange timidity took hold of him. This acquaintance could lead to a healing sobriety, but an aging man did not aspire to it, he too valued his intoxicated state. Ashenbach no longer cared about the duration of the holidays that he arranged for himself. Now he devoted all his strength not to art, but to a feeling that intoxicated him. He rose early to his place: Tadzio barely disappeared, the day seemed to him lived. But it was just beginning to dawn, when he was awakened by the memory of a hearty adventure. Ashenbach then sat down by the window and patiently waited for dawn.

Ashenbach soon saw that Tajio noticed his attention. Sometimes he looked up, and their eyes met. Ashenbach was once awarded a smile; he carried it away with him as a gift promising trouble. Sitting on a bench in the garden, he whispered words that were despicable, inconceivable here, but sacred and in spite of everything worthy: "I love you!".

In the fourth week of his stay here, Gustav von Aschenbach felt some kind of change. The number of guests, despite the fact that the season was in full swing, was clearly decreasing. Rumors of an epidemic appeared in German newspapers, but hotel staff denied everything, calling the city's disinfection precautionary measures by the police. Ashenbach felt an unaccountable satisfaction from this unkind secret. He only worried about one thing: no matter how Tadzio left. With horror, he realized that he did not know how he would live without him, and decided to remain silent about the secret that he accidentally learned.

Meetings with Tajio no longer satisfied Ashenbach; he chased, hunted him down. And yet it was impossible to say that he was suffering. His brain and heart were intoxicated. He obeyed the demon, who stamped his mind and dignity with his feet. Dumbfounded, Ashenbach wanted only one thing: relentlessly pursue the one who lit his blood, dream about him and whisper the gentle words of his shadow.

One evening, a small troupe of stray singers from the city gave a performance in the garden in front of the hotel. Ashenbach sat by the balustrade. His nerves revel in vulgar sounds and a vulgar-languid melody. He sat at ease, although he was internally tense, for Tajio was standing about five paces from him near the stone balustrade. Sometimes he turned over his left shoulder, as if he wanted to take by surprise the one who loved him. Shameful fear forced Ashenbach to lower his eyes. He had noticed more than once that the women who were taking care of Tajio had recalled the boy if he came close to him. This made Ashenbach's pride languish in hitherto unknown torment. Street actors began to raise money. When one of them approached Ashenbach, he again smelled disinfection. He asked the actor why Venice was being disinfected, and in response he heard only the official version.

The next day, Aschenbach made a new effort to find out the truth about the outside world. He went to an English travel agency and turned to the clerk with his fateful question. The clerk told the truth. An epidemic of Asian cholera came to Venice. The infection got into food and began to mow people in the narrow Venetian streets, and the premature heat favored it as much as possible. Cases of recovery were rare, eighty and a hundred sick died. But the fear of ruin turned out to be stronger than honest observance of international treaties and forced the city authorities to persist in the policy of silence. The people knew this. Crime grew on the streets of Venice, professional debauchery took on unprecedentedly impudent and unbridled forms.

The Englishman advised Ashenbach to leave Venice urgently. Ashenbach's first thought was to warn the Polish family about the danger. Then he will be allowed to touch the head of Tajio with his hand; then he will turn and escape from this swamp. At the same time, Aschenbach felt that he was infinitely far from seriously wanting such an outcome. This step would again make Ashenbach himself - that was what he was most afraid of now. Ashenbach had a terrible dream that night. He dreamed that he, submissive to the power of an alien god, was participating in a shameless orgy. From this dream, Ashenbach woke up shattered, submissively surrendering to the power of the demon.

The truth came to light, hotel guests hurriedly dispersed, but the lady with the pearls still remained here. Ashenbah, seized with passion, at times thought that flight and death would sweep away all living things around him, and he alone with the beautiful Tadzio would remain on this island. Ashenbach began to pick up bright, youthful details for his costume, wear precious stones and spray himself with perfumes. He changed clothes several times a day and spent a lot of time on it. In the face of voluptuous youth, he became disgusted with his own aging body. In the barber shop at the hotel, Ashenbahu dyed his hair and put makeup on his face. With a beating heart, he saw a young man in the mirror in the color of years. Now he was not afraid of anyone and openly pursued Tajio.

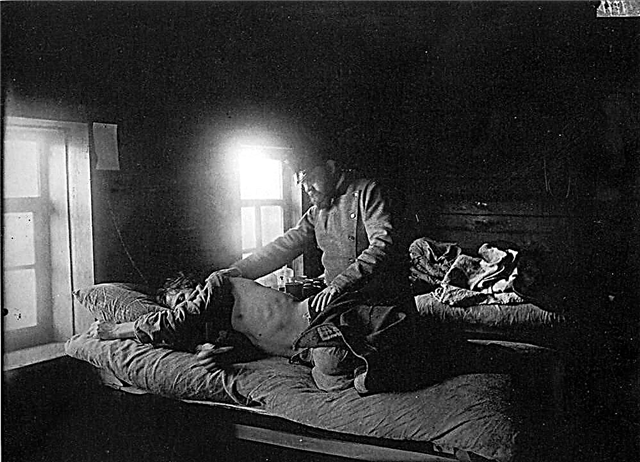

A few days later, Gustav von Aschenbach felt unwell. He tried to overcome bouts of nausea, which were accompanied by a sense of hopelessness. In the hall he saw a pile of suitcases - it was a Polish family leaving. The beach was inhospitable and deserted. Ashenbach, lying on a deck chair and covering his knees with a blanket, looked at him again. Suddenly, as if obeying a sudden impulse, Tajio turned around. The one who contemplated him sat like he did on the day that this twilight-gray gaze first met his gaze. Ashenbach’s head slowly turned around, as if repeating the boy’s movement, then rose to meet his gaze and fell to his chest. His face took on a sluggish, inward expression, like a person plunged into deep slumber. Ashenbah imagined that Tajio smiled at him, nodded and carried away into the boundless space. As always, he was about to follow him.

A few minutes passed before some people rushed to the aid of Ashenbach, who slipped on his side in his chair. On the same day, the shocked world reverently accepted the news of his death.

Life as a startup

Life as a startup