It so happened that in the last war year, a local resident Andrei Guskov returned secretly from the war to a distant village on the Angara. The deserter does not think that he will be met with open arms in his father’s house, but he believes and is not deceived in his wife’s understanding. Although his wife Nastena is afraid to admit it to herself, she understands with a flair that her husband has returned, there are several signs to that. Does she love him? Nasten did not marry for love, four years of her marriage were not so happy, but she is very devoted to her peasant, because, having left her parents early, she found protection and reliability for the first time in her house. “They conspired quickly: Nasten was spurred on by the fact that she was tired of living with her aunt in the workers, bending her back to someone else's family ...”

Nastena rushed into marriage as if into water - without too much thought: you still have to go out, few people do without it - why pull it? And what awaits her in the new family and in a strange village, was poorly represented. And it so happened that from the workers she got into the workers, only the yard is different, the economy is bigger and the demand is more strict. “Maybe the attitude to her in the new family would be better if she gave birth to a child, but there are no children.”

Childlessness also made Nasten endure everything. From childhood, she heard that a woman who was hollow without children was no longer a woman, but only half a dick. So, by the beginning of the war, nothing comes of the efforts of Nasten and Andrei. Guilty Nastena considers herself. “Only once, when Andrei, reproaching her, said something absolutely unbearable, she answered with insult that she still didn’t know which of them was the reason - she or he, she did not try other men. He beat her half to death. " And when Andrei is taken to the war, Nastya is even a little glad that she is left alone without the children, not like in other families. Letters from the front from Andrei come regularly, then from the hospital, where he gets injured too, maybe he will come on vacation soon; and suddenly there is no news for a long time, only once the village council chairman and the policeman go into the hut and ask to show correspondence. “Didn't he say anything more about himself?” - “No ... But what is the matter with him? Where is he?" “So we want to find out where he is.”

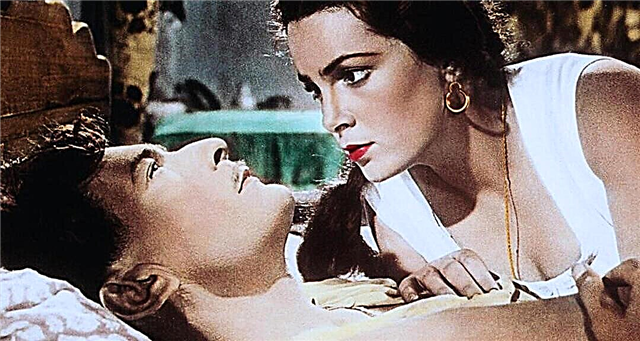

When the ax disappears in the Guskov’s family bath, only Nastena wonders if her husband has returned: “Who would ever think of a stranger to look under the floorboard?” And just in case, she leaves bread in the bathhouse, and once even drowns the bathhouse and meets in it the one she expects to see. The return of the spouse becomes her secret and is perceived by her as a cross. “Nasten believed that since Andrei left home, there was some kind of participation in her, she believed and was afraid that she probably lived for herself, and she waited: on, Nasten, take it don’t show it to anyone. ”

She readily comes to the aid of her husband, is ready to lie and steal for him, is ready to take the blame for the crime of which she is not guilty. In marriage, you have to accept both bad and good: “You and I have converged on a life together. When everything is good, it is easy to be together, when it is bad - that’s why people come together. ”

Frenzy and courage settles in Nasten’s soul - to fulfill her female duty to the end, she selflessly helps her husband, especially when she understands what she is carrying under the heart of his child. Meetings with her husband in the winter hut over the river, long mournful conversations about the hopelessness of their situation, hard work at home, settled insincerity in relations with the villagers - Nastena is ready for anything, understanding the inevitability of her fate. And although love for her husband is more a duty for her, she pulls her life strap with remarkable manpower.

Andrei was not a murderer, not a traitor, but merely a deserter who escaped from the hospital, from where they were not going to cure him, they were going to send him to the front. Having set himself on a vacation after a four-year absence at home, he cannot refuse the thought of returning. As a country man, not urban or military, he is already in the hospital in a situation from which one escape is escape. So it all turned out, it could have turned out differently, if he was firmer on his feet, but the reality is that in the world, in his village, in his country, he will not be forgiven. Realizing this, he wants to pull to the last, not thinking about his parents, his wife, and especially about the unborn child. The deeply personal that connects Nastena with Andrei conflicts with their way of life. Nastena cannot raise her eyes to those women who receive a funeral, cannot rejoice, as she would have rejoiced before when the neighboring men returned from the war. At a village holiday on the occasion of victory, she recalls Andrei with unexpected anger: “Because of him, because of him, she has no right, like everyone else, to rejoice in victory.” The runaway husband asked Nastena a difficult and insoluble question: who should she be with? She condemns Andrei, especially now, when the war is over and when it seems that he would have remained alive and unharmed, like everyone who survived, but, condemning him from time to time to anger, to hatred and despair, she retreats in despair: yes because she is his wife. And if so, it is necessary either to completely abandon him, jumping up on the fence with his cock: I am not me and not my fault, or go along with him to the end. Though on the chopping block. No wonder it is said: whoever marries someone will be born into that.

Noticing Nastena’s pregnancy, her former friends begin to chuckle at her, and the mother-in-law completely drives her out of the house. “It was not easy to endure the grasping and judgmental views of people - curious, suspicious, evil.” Forced to hide her feelings, to restrain them, Nastya is getting more and more exhausted, her fearlessness turns into a risk, into feelings, wasted in vain. It is they who push her toward suicide, draw her into the waters of the Angara, flickering, as if from a terrible and beautiful fairy tale of the river: “She is tired. Who would know how tired she is and how she wants to relax. ”